How hard can it be? Testing the dependability of AI detection tools

Students are using artificial intelligence to write essays and other assessment tasks, but can they fool the AI detection tools? Daniel Lee and Edward Palmer put a few to the test

You may also like

Public access to generative artificial intelligence (GAI) made a dramatic leap forward with the release of Open AI’s ChatGPT in November 2022. Students rapidly adopted the technology to assist them with their written assignments and universities reacted in a variety of ways, including trying to find ways to detect if students had used AI. A common plagiarism-detection tool used by universities is Turnitin, which, from April 2023, includes an AI detection feature. This led a team from the University of Adelaide’s Unit for Digital Learning and Society to test this AI-detection tool, and a few others, to see how easy it is for students to fool the system.

Testing Turnitin’s AI detection

To create a simulated sample of student work, ChatGPT was asked to write a critique of the 2004 Yi-Mou Zhang movie House of Flying Daggers. Turnitin’s detection tool successfully spotted the AI-generated text, returning a result of 100 per cent AI-generated content. ChatGPT was asked to rewrite the movie critique to make it “more humanlike”. The resulting output still did not trick the Turnitin detection tool. However, after ChatGPT was asked to rewrite the critique in the style of a 14-year-old school student – and then again, a fourth time, with “more random words” – things changed. With ChatGPT’s conclusion to this final attempt at the movie critique – “This flick is the bomb-diggity. You won’t want to miss it, bro!” – Turnitin was unable to detect the AI content, returning a 0 per cent AI content in the final test.

- Can we spot AI-written content?

- Will ChatGPT change our definitions of cheating?

- Collection: AI transformers like ChatGPT are here, so what next?

A second test used a sample 500-word essay composed by ChatGPT on the topic of academic integrity. The essay was then modified using strategies to replicate how a student might try to trick the AI detection: sentences were paraphrased and restructured, and a few spelling mistakes were deliberately included. The Turnitin AI-detection result went from 100 per cent for the ChatGPT-generated sample to 39 per cent for the modified essay.

To further replicate how some students are known to be using AI, a third test was conducted in which ChatGPT was asked to improve paragraphs that were known to be originally written by a human to make them sound “more academic”. The first paragraph was extracted from one of the researchers’ own previous journal publications, and the second stage used two paragraphs taken from a transcription of one of their oral presentations at an academic conference. In both cases, Turnitin was unable to detect AI-generated content in these submissions.

Testing online AI detection tools

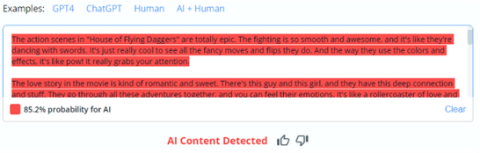

The research team then tested some of the freely available online AI-detection tools using the same tests and samples, to wildly varying results. Some tools proved reasonably reliable. However, in other cases, the AI-detection tools returned a lower score for the AI-generated or modified samples than the original human-written samples. The most reliable tool was found to be Copyleaks, with a result of 85.2 per cent probability for AI content for the movie critique written like a 14-year-old school student, and 73.1 per cent probability for AI content for the essay even after it had been altered by a human.

However, some tools returned peculiar results, including a false positive from Content at Scale, which returned a 99.9 per cent AI content score on the ChatGPT-assisted human-generated paragraph.

It is important to note that these tests were conducted in July and August 2023. As the tools and ChatGPT evolve, these figures are likely to change. None of the AI-detection tools proved extremely reliable and even the best of them could be easily tricked. AI-detection tools are still in their infancy and will learn to improve just as AI content generators will learn. A Cornell University report, Can AI-Generated Text be Reliably Detected?, reminds us: “As language models become more sophisticated and better at emulating human text, the performance of even the best-possible detector decreases.” It is unknown how this battle between the two technologies will unfold.

It is recommended that educators test AI’s ability to complete their own assessment tasks and consider ways students might be using ChatGPT or other AI generators. Testing AI generators using a range of AI-detection tools will give educators a wealth of useful information about the design of their assessments. They will be able to ascertain how easy each assessment task is for students to use generative AI to assist in producing work. It will also give valuable information regarding which types of assessments are most resilient to AI.

Furthermore, by doing this, educators will familiarise themselves with the red flags for AI-generated content within their own assessment portfolios. The results of this study suggest that Copyleaks would be a valid online tool to begin this process. But the real takeaway is that we should assume students will be able to break any AI-detection tools, regardless of their sophistication. The goal for educators is to now design assessments that encourage and test learning rigorously in an AI world. This is a challenging sector-wide task – but one that is long overdue.

Daniel Lee is postdoctoral researcher in the Unit for Digital Learning and Society and Edward Palmer is associate professor, both in the School of Education at the University of Adelaide.

If you’d like advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered direct to your inbox each week, sign up for the Campus newsletter.