Using reflective practice to support postgraduate studies in the biosciences

Small-group workshops create space for postgraduate researchers to share ways to manage stress, impostor syndrome, feelings of isolation and student-supervisor relationships. Here’s how to set up a programme

You may also like

Studying for a PhD should be considered the ultimate sign of passion for your subject. That dedication, however, also involves gruelling day-to-day work: long hours, tight deadlines and a competitive environment, with little financial reward. All this requires hard work, resilience and patience to overcome. The skills developed along the way are vital for careers in STEM, but mastering them can have a substantial impact on the well-being of individuals.

It is a sad fact that postgraduate students are six times more likely to experience depression and anxiety compared with the general population, and this is obvious in doctoral training programmes up and down the UK. Following the outcome of an in-house well-being survey by the leaders of the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council-funded South Coast biology doctoral training partnership (SoCoBioDTP) in 2021, it became clear to our well-being lead, and co-author here, Jenny Tullet, that PhD students needed a new skill set to help them with these challenges.

Universities can signpost PhD students to methods of support such as counselling services or well-being classes, but her approach was different. We were encouraged to sign up to a series of bespoke workshops. The Reflexivity in Research workshops built on work by the international Women in Supramolecular Chemistry group and was adapted to the requirements of biologists undertaking a PhD in a UK-based university.

- How to make public engagement work for early career academics

- Why every student (and researcher) should know about evidence synthesis

- How to turn an average collaboration into a dream team

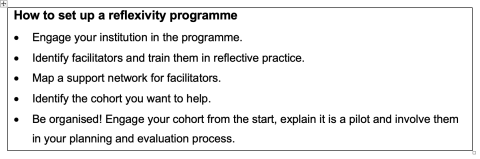

We worked online in small groups of students, guided by a trained facilitator, to reflect on our PhD journey and share our experiences. Each of the six sessions was one-hour long and organised around a key topic (see table below). We were asked to bring thoughts on that topic to the session and to listen to those of others.

| Key topics in the Reflexivity in Research workshops |

| Who are you as a bioscientist? An opportunity for students to discuss their interests and expectations. Creates space to talk about belonging and impostor syndrome. |

| PhD student life expectations: What is expected of you from yourself and others around you? This workshop focused on professional or personal relationship problems that might impact PhD progress. |

| Pressure and stress management: How does it feel to be under pressure, and how do you cope? This session focused on work-life balance and developing strategies to manage stress. |

Within our groups, the facilitator initiated the conversation, ensured confidentiality and encouraged others in the group to engage and lead the discussion. This created a safe space for all to contribute and share advice, which improved our understanding, encouraged us to share and built empathy towards others.

Facilitators were personable, encouraging and warm in their manner, as well as being organised and clear. Although from the same scientific discipline as us (so they could easily grasp the situations we discussed), the facilitators were not our direct colleagues. This fostered a confidential and constructive environment that allowed us to share openly (see below). A creative approach was also encouraged, and we brought a personal twist or personal item to the sessions. Although the approach took us out of our comfort zone (being unusual in a STEM discipline), it acted as an equaliser and helped us to relate better to each other on a personal level.

Bringing our thoughts together in this way provided reassurance that we were not alone. Few of us knew our role in the workplace, many of us felt inadequate, and we shared difficulties with relationships within our labs. Key themes reflected the challenges that PhD students face: how to manage pressure and stress; impostor syndrome; how to approach and maintain professional, productive and healthy student-supervisor relationships; and the importance of trust and transparency in the workplace. It felt less isolating and comforting to know that someone else understood, and that our struggles were often universal and, in some instances, a reflection of the system itself.

As in many scientific experiments, the goal is often in the solutions. Focusing on what we could do (rather than what we could not) helped to alleviate many of the symptoms we had. We advised each other on ways to think differently about our experiences, and what steps we could take to address problems. Now, we regularly keep in touch with each other, demonstrating the power of emotional connection and the sense of belonging created by the programme.

Overall, the programme itself had overwhelming positive feedback from staff and students alike. We have built up a toolkit that has helped us to remain focused on what is important and find mechanisms to channel our energy to support this. This is an ongoing piece of work, but understanding who we are and what our needs are keeps us sane and makes us better scientists.

So, really, looking after yourself may be the greatest skill you can gain as a researcher.

Jo Haszczyn and Johanna Fish are postgraduate researchers in the School of Biological Sciences at the University of Southampton.

Jennifer Tullet is a reader in the biology of ageing, director of postgraduate studies in biosciences at the University of Kent and is an academic and well-being lead for the SoCoBio DTP.

If you would like advice and insight from academics and university staff delivered direct to your inbox each week, sign up for the Campus newsletter.